Roundtable talk in a “NBL” magazine

アジャイル・ガバナンスとソーシャル・イノベーション

デジタル技術の急速な発達と、それに伴う社会構造の変化(Cyber Physical System)は企業や政府、個人ができることを広げ、社会課題を解決する可能性を秘める。その実現のためには、課題の適切な発見、世代を超えた人々による合意形成と知見のシンクロなどの論点がある。企業、政府、個人・コミュニティが協働してより良く取り組むためのヒントについて、オードリー・タン(唐鳳)台湾デジタル担当大臣へ9つのQuestionとともにうかがった。聞き手には、この大きな課題について「アジャイル・ガバナンス」を提唱し、関連する2つのガバナンス・イノベーション報告書の取りまとめ*をリードされた宍戸常寿教授(東京大学)、稲谷龍彦教授(京都大学)、羽深宏樹弁護士(経済産業省)にお願いし、タン大臣とのご議論をいただいた。

*経済産業省「GOVERNANCE INNOVATION: Society5.0の実現に向けた法とアーキテクチャのリ・デザイン」報告書

https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/mono_info_service/governance_model_kento/20200713_report.html

「GOVERNANCE INNOVATION Ver.2: アジャイル・ガバナンスのデザインと実装に向けて」報告書

https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/mono_info_service/governance_model_kento/20210730_report.html

Roundtable talk in a “NBL” magazine

“Agile Governance and Social Innovation”

(The English full transcript is available at the end of this page)

The rapid development of digital technology and the resulting changes in social structure (Cyber Physical System) have the potential to expand the scope of what companies, governments, and individuals can do to solve social issues. In order to achieve this, there are several issues that need to be addressed, such as the appropriate discovery of issues, consensus building among people of different generations, and the synchronization of knowledge. Experts from Japan asked Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s Digital Minister, nine questions on how businesses, governments, individuals and communities can work together to better tackle arising issues in the digitalized society. The interviewers are Professor George Shishido (University of Tokyo), Professor Tatsuhiko Inatani (Kyoto University), and Attorney Hiroki Habuka (METI: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), who advocated “agile governance” in the report published by METI, titled “Governance Innovation”*. The English full transcript of the talk is available at the bottom of this page.

* “GOVERNANCE INNOVATION: Redesigning Law and Architecture for Society 5.0” (METI, 2020)

https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2020/0713_001.html

“GOVERNANCE INNOVATION Ver. 2: A Guide to Designing and Implementing Agile Governance” (METI, 2021)

https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2021/0730_001.html

INFORMATION

下記の日本語版記事(PDF)の掲載号では、「アジャイル・ガバナンスを担う企業の役割」と題して、上記3名の先生方と白坂成功教授(慶應義塾大学大学院システムデザイン・マネジメント研究科教授)、水野祐弁護士(シティライツ法律事務所)、渡部友一郎弁護士(Airbnb Lead Counsel日本法務本部長)による、経済安全保障対応、企業によるルールメイキング、インセンティブとしての企業制裁制度のあり方や、合意形成の本質などについてご議論いただいた座談会も掲載しています。

これを機にぜひ「NBL」のご購読をご検討いただけますと幸いです。

【購読お申込みはこちらから】

https://www.shojihomu.co.jp/paymentguide/form

(つながりにくい場合には、大変に恐れ入りますがメール(order@shojihomu.co.jp)、お電話(03-5614-5651)にてご連絡くださいますようお願い申し上げます。)

「NBL(New Business Law)」は、株式会社商事法務が発行する法律実務誌。経済と法律、企業実務を架橋すべく、立案担当者による新法・改正法解説、研究者や実務家による実務上の最新論点の分析・解説等だけでなく、近く課題となるテーマについての展望・提案を主な内容としております(毎月1日・15日発行、直接購読制、年間30,800円(税込)/半年15,950円(税込))。

日本語版記事(PDF) NBL 1209号(2022.1.1号掲載)

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to DearFlip WordPress Flipbook Plugin Help documentation.

Interview with Minister Audrey Tang

Agile Governance and Social Innovation

Thursday, October 28, 2021

Interviewee:

Minister Audrey Tang (Digital Minister of Taiwan)

Participants:

Prof. George Shishido (Professor, The Graduate Schools for Law and Politics, The University of Tokyo)

Prof. Tatsuhiko Inatani (Professor, Graduate School of Law, Kyoto University)

Mr. Hiroki Habuka (Deputy Director for Global Digital Governance, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Japan)

Introduction

(Habuka) Today, I would like to talk about governance in the digitalized society with Minister Tang. In Japan, we defined “Society 5.0” as a human-centered society where high integration of cyberspace and physical space can promote economic growth and solve social issues. In the process of pursuing Society 5.0, we found that in order to implement innovation in society, it is necessary not only to develop technologies, but also to have such technologies accepted by society as something that improves people’s happiness or liberty. This is what governance is all about. We defined “governance” as the design and operation of technical, organizational, and societal systems by stakeholders with the aim of maximizing positive impacts on society while managing risks at a level acceptable to stakeholders. In this way, “governance” is broadly defined to include all institutions and mechanisms for maximizing positive impacts of innovation, including regulatory governance systems and corporate governance, the democratic systems, market mechanisms, and also the technologies used for governance.

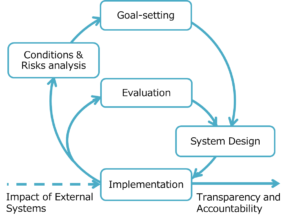

In traditional governance, the government plays a central role in establishing and enforcing rules, and businesses and citizens were subject to those rules or enforcement processes. This vertical model is based on the assumption that society is relatively simple and predictable, and that a single entity such as the government can prescribe appropriate rules. However, a society based on digital technology is extremely fast-changing, complex, and uncertain. In such a society, it is difficult for the government to keep up with the speed of change. For this reason, a decentralized governance model that emphasizes horizontal relationships among stakeholders such as businesses, individuals, communities, and the government, is considered necessary. This is why we proposed the “agile governance” framework. The framework is composed of two main pillars. The first pillar is “agile governance cycles” and the second pillar is “multi-stakeholder approach.” Let me explain in this order.

#1

First, agile governance cycles are the double cycles as indicated in this slide. The inner smaller cycle is the so-called PCDA or plan-do-check-act cycle. This is often used for business management. However, it is not enough to run the PDCA only to achieve the governance goals because the environment, risks, and goals are continuously changing in a digitalized society. Therefore, we placed the larger outer cycle that means the continuous “conditions and risk analysis” and “goal-setting” prior to “system design”. Also, in order to realize the multi-stakeholder model, which I will mention next, sufficient “transparency and accountability” will be the key. This is the right-bottom line. In the agile governance model, each stakeholder is expected to run these cycles.

#2

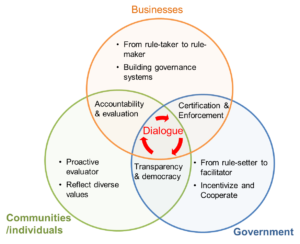

The second pillar is the multi-stakeholder approach. The new governance model needs to be one in which multi-stakeholders formulate rules and solve problems in a cooperative manner rather than one in which a single government sets uniform rules. This diagram indicates how the role of each stakeholder should change in Society 5.0. Namely, the “government” will serve as a facilitator of multi-stakeholder rulemaking and a provider of fundamental infrastructure or standards rather than the sole provider of rules or systems. “Businesses,” on the other hand, will become active designers of rules through providing self-regulations and designing digital architecture rather than passive followers of given regulations. Finally, “communities and individuals” can become more than vulnerable actors who lack sufficient information. They will become participants of governance who are able to actively communicate their values and evaluations to society or the government.

On top of that, the agile governance model calls for the “governance of governance,” which is the design of an overall governance architecture that shows how multiple governance mechanisms by each stakeholder should be combined to achieve certain goals.

After reading Minister Tang’s books and articles, and watching presentations, we found that there are a lot of common approaches between us. For example, we both address the importance of a multi-stakeholder approach and agile update of governance, as well as emphasis on transparency and accountability. Further, I found that Taiwan has already adopted cutting-edge platforms to implement the multi-stakeholder approach and agile update of governance mechanisms. Therefore, it is our biggest honor to exchange views and opinions on “agile governance” with you today.

Q&A

Q1

(Habuka) First of all, I would like to ask your opinion on our agile governance model. What do you think about the model — do you agree or disagree, and why?

(Tang) Well, I really like your summary. You first talked about the iterative cycle that is more like time-based pace of agile approach, and then you talked about multi-stakeholder collaboration or, in your words, governance of governance – “collaborative governance” is a more widely-used term, but I think it is essentially the same thing. So, I guess calling it “agile governance” instead of “agile co-governance” or something basically means that, in your jurisdiction, you want to focus on the time aspect. Whereas, in my jurisdiction, we are already pretty agile, time-wise, so we want to expand more on the multi-stakeholder aspect which is why I mostly say collaborative or co-governance, but at the end of the day, these two are like yin and yang. You cannot really do one without doing the other one because if you just iterate within your organization, then it becomes a normal PDCA cycle and there is no innovation to speak of when all your internal goals are not checked and balanced by external multi-stakeholders, and when we want to talk with businesses in the social sector, well, they all move under a faster speed than our four-year election cycle or yearly budgets, so by nature, we need to be more agile if we want to make co-governing multi-stakeholder. So, I think these two aspects are really one and the same. If you start practicing one, you probably practice the other, too. It is just on the emphasis or on like the accent – which vowel you stress more when you are presenting it – and I think it is quite isomorphic to the kind of collaborative governance that we are doing in Taiwan.

(Habuka) I totally agree that agile governance and collaborative governance have to work together simultaneously. The question is how to actually do that. I see a lot of good practices in Taiwan, and in the following questions, I would like to ask you how you have implemented the concept into practice.

(Shishido) I would like to add just a comment. In Japan, the speed of changing regulations is much slower than in Taiwan.

(Tang) That is right.

(Shishido) So, we would like to emphasize the speed in a PDCA cycle.

(Tang) Yes, and I think this is really a key issue because Taiwan uses the same Germany-inspired continental law system, so theoretically we should be operating on the same kind of constitutional law-mandated cycles of the written text defining the scope of each sector and so on, but in practice, we use a lot more regulations and interpretations than the laws. We tend to say in the law that “this part” will be defined by a regulation, and then because our regulations are co-creative, people starting a petition have this understanding that the parliament has already carved out a sandbox or so for various different swarm-like approaches to take effect in the defined scope of the more basic and more abstract law. So, by basically a blessing or a baptizing, the innovations in the shorter cycle within the continental law system, we can rest assured that the basic privacy or human rights and so on are not violated because these are the bedrocks defined in the law strata, but more and more things are now being worked on the regulation interpretation kind of like the Layer 2 of Ethereum. It is faster for iterate, but still it is secure by the main Layer 1 protocols.

(Shishido) Thank you. Very interesting.

Q2

(Habuka) Thank you. Let us move on to Question 2. Our next question is about the goals of governance. The first step in conducting the agile governance cycle is “goal setting” — to set out what value we want to achieve through governance. Nowadays, there are a variety of goals to be achieved, including not only economic growth, but also human rights, sustainability, or inclusion, etc. In addition, the number of stakeholders related to these goals has become very large and difficult to identify sometimes. So, in some cases, the interests of stakeholders may conflict with each other and it is difficult to reach a consensus among all stakeholders. How should government, businesses, or communities and individuals set their goals of governance and balance them?

(Tang) Well, if sustainability is the overarching value, then we must note that it is for the future generations which means the bulk of stakeholders have not been born yet, and so it is not possible to consult like seven generations down the line – the humanity of the future – of what to do today. Our “good enough” proxy is to be a “good enough” ancestor. “Good enough” ancestor, to me, means not foreclosing possibilities of future generations. It is not a bad ancestor that destroys the Earth – then, of course there is no future generations – but it is not a perfect ancestor that designs or over-designs everything so that the next generation has no room to innovate either. So, basically it is the idea of co-creative design with the hope that our next generation will enjoy even more freedom – free from scarcity, free from fear, free from the nation-to-nation conflicts, and so on – compared to our generation, and therefore our decisions, while making the current generation prosper of course – that is human nature – should always be weighed against the interest of the possibility of creation of future human generations. So, I think for most people, the longer horizon actually makes it easier to agree on “good enough” consensus.

If you think only about the next quarter, the business interests of course will conflict with the environmental interests, but if you think 30 years or 50 years down the line, interestingly most business interests will align with the environmental interests because if the environment gets destroyed in 20 years’ time, there is no business to speak of, so the longer term or the longer horizon that a governance system can prompt its constituents and stakeholders to think, then the more successful we will be to get “good enough” consensus on values, as well as being “good enough” ancestors. So, I think the government’s goal, far from being a monopoly on setting the facilitation of those public infrastructures in which people act with a longer horizon and more pro-socially, should be a collaborative design with anyone in the social or economic sectors striving toward the same pro-social public infrastructures in which the people will naturally communicate toward such longer termism.

It is a very simple idea, but I spent quite some time to get into the details because the language we use is overly-abstract for this, so I needed to kind of chart a precise design.

(Habuka) I understand that your idea is to introduce the dimension of time frames to overcome the current conflict of interest. I think it is a great idea to harmonize people’s opinions.

(Tang) Yes, and I would also say that the proportional length of your two cycles suggest that maybe the PDCA – the smaller cycle of conflict resolution and accountability and so on – is maybe at half the time frame of setting new goals, but in my mind, this one, the inner one, should be much faster and the outer one should be much longer. That is to say the PDCA should happen on an almost daily or even hourly with OpenAPI even per second approach, but the larger goal-setting needs to take the steps of generational thinking. That is to say we cannot do our conditions and risks analysis within our generation of course, but the goal-setting part, in my mind, is actually far longer, and we just get the part of the puzzle that could be realized within our generation into the system design while consciously leaving some open research problems open.

(Habuka) Great insight, I totally agree.

(Inatani) It is a very interesting idea. I am afraid that actually in Japan, as you know, the population is very aged and maybe there is a kind of division between older persons and younger persons, and the elderly population is bigger than the younger population, and so it is very difficult for us to make the elderly have a more future-oriented mindset, as you mentioned, that may elicit more public, well-oriented thinking or other more productive mindsets.

(Tang) Yes, definitely. I totally agree because Taiwan is becoming an aging society, too.

(Inatani) From your point of view, what is your idea in regards to this problem? It is very challenging for us to make the elderly more concerned about the future.

(Tang) I would like to say that most elderly people past their retirement age in Taiwan still actively want to contribute to democracy. That is to say the voting turnout, especially the referendum turnout, is very high in senior citizens, and they are the age group that is second only to 16-17 years old when it comes to citizens’ initiatives on the joint platform and so on. So, in Taiwan, we are looking at an aging demographic, but as they do not have the long work hours, they maybe still work as consultants or as local community organizers, but the fact is that they have much more free time to philosophize and to think about basic values and so on, so the question is “How do we channel such wisdom of the elderly into our daily practice of democratic decision-making?” for if they are feeling that they are left behind that they must chase this digital gap or things like that, then basically they enter this very reactive mood and become extra conservative when it comes to value setting.

If you limit their expression of their ideas to just like three bits every four years, which is called voting, then of course they will fossilize into the most conservative of their thinking. I am not saying that conserving culture or conserving nature is bad. It is actually pretty good, but as you said, it is about entertaining new possibilities. In my opinion, that is most easily realized if you give them more bits into participation. Participatory budget is a great way for the young people to think of great ideas and the elderly decide how to allocate resources to make it happen. As I understand, the regional revitalization plan also couples nomadic innovators with the local resourceful community organizers who are much more senior – maybe two generations senior – compared to those young innovators and so on. So, I think the 17-year-olds and the 70-year-olds are actually natural allies in thinking about long-termism.

If we put them in opposition or at odds with each other, then they cancel each other out and democracy does not have this inclusive diversity to work with, but if they become natural allies through mechanism design or through the “good enough” consensus, there is a reliably-produced – for example, in Taiwan, marriage equality. We produced such a consensus so that individuals wed, but families do not. That has united both generations on both ends so that they can work on something that they can all live with.

(Inatani) Okay. This is great. So, maybe we need a good interface of democracy for adapting goals for all elderly. That is very good.

(Tang) That is right. To maximize the use of their cognitive surplus, so to speak.

(Inatani) Yes, thank you.

Q3

(Habuka) Thank you. Actually, that is exactly our next question – how to design the governance structure to achieve these goals. First, I would like to ask about the democratic system which is the foundation of the entire governance model. I heard in Taiwan that there is a system whereby the government always takes actions on matters for which more than 5,000 signatures from citizens have been collected. This kind of direct participatory democracy could be the ideal form of democracy. However, it has also been said that direct participatory democracy sometimes has problems with the quality of the debate or the stability of public services. How can digital technology be used to overcome these challenges of direct participatory democracy and realize a high quality of democracy?

(Tang) Well, by focusing on the leftmost arrows from “implementation” to “risk analysis,” and from “implementation” to “evaluation,” because on these two particular arrows in your cycle, representativeness is not a concern. Stakeholders ineligible to speak are the people who are suffering because of the current implementation. Anyone who is caught between what is in reality and what the current regulations say should be, the reality is ineligible to talk about what is going wrong with the system and what risk there is inherently in the current design and the conditions in which we can make it a better goal or a better realization of the goals, but it does not say anything about system design. It does not say anything about the implementation. It does not say anything about a particular form that it should take to resolve this dilemma. So, basically we are just mapping out the pain points or the subjective feelings, and on the subjective feelings, there is no “quality of debate” issue because everyone is an expert in describing their own qualia or their own subjective experience, and so by focusing on the feelings and letting the feelings to resonate with one another into ideas, and we stop right there. We do not presume to replace the professional public servants or the parliament, for that matter, when taking those ideas into implementation.

By focusing strictly on, say, the first diamond of the Double Diamond model of design thinking, it increases the kind of range of the radar for the professional representatives and public servants to look at the map of the issues to work with, and also it can empower everyone to think outside of the local optimum because for the structural changes, there is a need to elevate people outside of the local optimum. It cannot come from the unilateral movement from anyone within the same structure because otherwise it would be Pareto improvement and you have already resolved it. The reason why we have structural problems is that nobody can unilaterally resolve them, but if we open up the conversation to people who are suffering from the pain and if we empower them, they can describe their local hack or their local ad hoc solutions that actually lifts us out of this force equilibrium, and then the governments or the businesses in the social sector that participate in this multi-stakeholder panel could just readily amplify this catalyzing solution to a longer-term implementation, and of course maintaining the operational cost necessary associated with it.

I called this “reverse procurement.” Instead of the professional public servants thinking of an idea and the individuals in the citizenry implementing it, it is the other way around. It is the individual citizens elevating their local hack into such an “ideathon” or “hackathon,” and then the government becomes like a vendor and implements those brilliant social innovations. That is how our mask rationing, our contact tracing system, and our vaccine reservation system came about. It is not my brilliant idea. These are some smaller-scale ideas from some civil society hacker.

(Habuka) The reverse procurement idea is a really great idea. Maybe when we talk about deliberative democracy, we imagine that you have to get all stakeholders together at one time and conclude discussion, and once concluded, you should never change the outcome. That is maybe the old type of deliberative democracy, but in a digitalized society, you should pursue a lightertouch and agile, fast-updating democracy.

(Tang) Well, “never” is very long time frame. I think even constitutional citizen assemblies do not say, “Never.” In their constitutional outputs, they allow for amendments. So, I think it is important here to denote the actual implementation and feedback cycle in precise days. In citizens’ initiatives’ 5,000 signatures, the pace is 60 days. We collect the venture for 60 days. If it meets the threshold, the response will come within 60 days, and after the initial collaborative meeting, a decisive action point-by-point or the explanation of why it is not possible point-by-point will be delivered within 60 days, so it is a very fixed pace and the citizens can then take the parts that government says, “It is just simply impossible for us to do,” but it does not preclude the citizens to start a new initiative, crowdfunding or crowdsourcing, to realize those, because previously people did not realize the government has the will but not the budget, or has the budget but not the will, to do something, but through a collaborative meeting and this, as I said, 60-day cycle, it becomes a thing of mutual accountability.

That is to say something that is best for the citizens to do like independent journalistic fact-checking. Maybe the government should not do that. If the government does that, we risk becoming a kind of state monopoly on truth which is a very bad idea, but for the government to speak out in a collaborative meeting that maybe it is better for the citizens to do that, we do not need all the journalism practitioners in the same room. We just need someone that can take this idea back to their community and start a crowdfunding or crowdsourcing event. So, I do not think this is about getting everybody in the same room, but it is about getting the entire record radically transparent so people late to the party can nevertheless resume the context on top of which their contributions can be made visible.

Q4

(Habuka) Actually, our next question was “How will the roles of governments, corporations, and citizens change if the ‘public’ function is extended to include all these stakeholders?” Maybe you have already answered about how citizens can contribute to public policymaking, but do you have any other perspectives about how the business sector can cooperate with public policymaking?

(Tang) Certainly. I believe that if there is a strong norm or habit that is already co-created and agreed by such multi-stakeholder panels, then the social sector will already amplify this norm. For example, wearing a mask to express one’s feelings about the color rainbow or the color pink or something. It is well-established in Taiwan and that is something that the social sector produced – not rules and regulations, but rather the norms. Once the norm is produced, of course we have got a lot of people with commercial interests to produce the most fashionable, while still statement-making, rainbow mask and things like that. We have from the Tokyo Olympic badminton game, this court, “one in” picture that decisively settled the game. That has been symbolized in numerous mask designs and so on. So, what I am having in mind is that the commercial interests, if they are piggy-backing on top of a norm that is already established as “good enough” and pro-social, then it is just a normal function of the market to make good mechanisms that can scale out and scale up such norms, and it provides a kind of natural vehicle on top of which those ideas will spread.

Our main problem previous to the HR governance model is that the company had no way to know where the norm is going, so they risk producing something that will face social sanctions just a month a later or they risk producing something that is only fruitful for the consumers but at negative externalities to other people which may go back and haunt them, even without social sanctions, that they may be subject to fines and penalties and so on once those externalities are discovered and so on. So, for the business to participate in this model, I believe this is mostly a risk-reducing move. The more they participate just like in international standard setting and so on – the more they participate in the standard-setting community, the less likely that they will produce something that is risky.

Q5

(Habuka) I see. Yes, that is a good combination of democracy mechanisms, social norms, and market mechanisms. You talked about social norms, which leads us to the next question. Social norms are not always reasonable or sometimes very conservative.

(Tang) But they are normal.

(Habuka) Yes, and it sometimes impedes adoption of technology for governance. Technological solutions, such as the use of AI to detect abnormalities and drones to inspect infrastructure, for example, are enabling machines to replace governance by humans. On the other hand, governance based on these new technologies takes time to gain trust from people, which makes for delays in the revision of rules. What do you think is necessary to promote the adoption of new technologies for governance? Especially on dialogue between policymakers and engineers for forming optimal rules?

(Tang) I think there is technology and there is tech. The kind of backlash against overarching, almost authoritarian, certainly centralizing technological solutions are symbolized by the English words, “Big Tech,” but just like math is not mathematics, as my primary school teacher would tell me. “Tech” is not technology. “Tech” is just one small part of the entire technology scene. For example, “tech” would not include open space technology, dynamic facilitation, and non-violent communication, but these are all social technologies. Democracy itself is a social technology, but it is not included as “tech.” So, I think really the idea to move away from tech solutionism is to actually bring about the social technologies to the forefront.

We apply a lot of social innovations and social technologies, but they are not even the same attention in policymakers’ cycles as industrial innovations and like industrial applications of the latest patents, mostly because the social norms are not patentable, otherwise they do not become norms, but nevertheless they are essential in providing more empowering and more assistive ways of doing things. For example – I will use one very concrete example. Our contact tracing system, the 1922 SMS, is not technologically superior. It is not a cutting-edge design. It is certainly not powered by blockchain or artificial intelligence or 5G or whatever. It is just SMS which is 2G, the last I checked, but it has the advantage that everyone understands how SMS works and everyone understands how QR code works. We even print the content of the QR code, the 15 digits, on the same poster, so if your camera breaks, you can still manual text the 15 digits which is a random code because everyone can get one for themselves to verify that to your local telecom operator as a post-it note, and we make it very clear that the quarter billion or so SMSs sent, only around 11 million have been collected by the contact tracers, and with mutual accountability, you can still use an SMS and a one-time PIN to get the history of the past 28 days of which municipalities and which contact tracer got your SMS.

As I mentioned, this system is a social innovation with no cutting-edge industrial innovation component at all, but it succeeded precisely because it utilizes not cutting-edge technologies and therefore maximizes understandability and therefore trust. So, governance based on new tech of course take time to gain trust, but governance based on tried and true, or as the old saying goes, the appropriate tech, it is appropriate because anyone can appropriate it. It is remixable. Remixable, appropriate technology with cutting-edge social innovations can actually gain trust much more quickly and also in a much more stable fashion because people can try it for themselves and if it breaks, they keep both pieces. They can innovate beyond the limitations of the original designer’s thinking.

(Habuka) Thank you, I totally agree that tech is not only about technology and social tech innovation is sometimes much more important.

(Shishido) I would like to ask a question. My question is, how can we synchronize the technology code and our political code in law? In Japan, usually engineers say, “I cannot understand what you mean, Professor” and we cannot understand what the engineer is really thinking. I suppose you are a good translator for both experts and citizens, Minister Tang, so please share some of your advice on this matter.

(Tang) Yes, I think it is about building a ladder of expertise. It is not about a few elites mastering the language of both worlds. I am not an expert lawmaker. My understanding of the legal principles are very shaky, but I do have pretty good co-founders in my office who are just a level above me when it comes to legal understanding, but they are good to explain to me. Then, they can consult people who are even more professional in legal theory and so on which is also in my office. If they want, they can also reach to the like truly constitutional court judge level of people who of course do not have the time to explain to me all day long, but through those two or three layers of intermediacy, we can get pretty good consistent translations going. So, this is not about someone playing the role of a mediator. This is about the competence of contributing to dialogues which is part of our both lifelong and basic education.

The idea is very simple. If you are empowered to create some spreadsheet formulas to simplify your daily work, then the next time somebody says, “Oh, this is just a functional programming – a lambda or something,” then you will note, “Oh, this is just actually an ‘equal sign’ in your spreadsheet,” so that you do have this working firsthand experience of writing functional programs without being a professional functional programmer, and then you will get connected to the community that can connect better above this ladder.

The same goes for the people’s initiatives on the joint petition platform. Of course, they have no idea what an interpretation or regulation versus a law versus a constitutional amendment means, but in the process of starting a petition, these are kind of co-created workshops that will then imbue in them the capability to see it from the lawmaker’s standpoint without being a professional lawmaker themselves. Then, the next time anyone in their community proposes something, they will be able to find the right connections to explain the level of law, whether it is municipal law or central government law and so on, to their community members. So, when both sides of the community have sufficient social networking links through each other’s community, then the collective intelligence resolves this issue almost automatically, and so I think this is interesting because this is precisely what the word “synchronization” means.

What we need is not some individual person playing the role because that will not be synchronized. It will actually be asynchronous. It would be a batch processing like in Minority Report – three people batch processing forecasting the future. But rather, the intelligence would be distributed in the collective intelligence. It requires us to rethink the role of professionals from becoming a central node of knowledge and standardized answers toward becoming facilitators and connectors between existing networks and also creating or making new networks because intelligence is in those human networks and not in anyone’s brain.

(Shishido) Thank you. That paints a very vivid image. Thank you very much.

Q6

(Habuka) Our next question is about transparency and accountability. They are very important for agile governance or collaborative governance, but information about complex systems and technologies is difficult for many people to understand, even when the facts are presented as they are. So, when governments and companies try to ensure transparency and accountability, what should they do to make sure that the appropriate explanation is conveyed to citizens and users?

(Tang) As I mentioned, it should be conveyed on an on-demand basis so that nobody teaches, but everybody learns together.

(Habuka) So, first make something, experiment with that, and then more people can evaluate.

(Tang) That is how we learn cooking. We do not learn cooking from memorizing chemical formulas.

(Habuka) Exactly.

(Inatani) Yes, actually I am very impressed with the former conversation with yourself and Prof. Shishido. It seems to me very impressive because, actually, we do not synchronize law and technology itself. All we can do is collaborate with people.

(Tang) Exactly.

(Inatani) So, we need a good interface to connect people. That is our first step. Actually, our society is diseased by many sectionalrism in companies, bureaucrats, and some other sectors of society. It is very fragmented now I think, so I think we should use technologies and a good interface to reconnect them in order to rebuild a more flexible and more open society, which is maybe the first step we should adopt. That is my impression. Thank you so much.

(Tang) Yes, definitely. I think social technologists are like this glass – this assistive technology. It is aligned to my interest. It is aligned to my eyesight. It allows me to see you better, but it does not presume to express or see on behalf of me or push advertisements to my retina. Also, if it breaks, I can repair it myself. I can bring it to the repairperson down the street. We do not have to pay a central patent registry 100 or one million dollars just to get a new licensed copy of this glass, and just like the SMS/QR code example, the principle is very well-understood by the people wearing this, so it is an empowering device for a disabled person – me with my disabled eyesight – rather than an overarching top-down authoritarian device.

(Inatani) Yes. Good. Thank you.

Q7

(Habuka) Let us move on to the next question about evaluation. Evaluating governance systems – whether goals are being met by current regulations or corporate practices – often requires specialized expertise, and values such as privacy and security are difficult to quantify in the first place. It depends on the person – how much risk she or he is willing to take. So, how and by whom can we determine whether government objectives are being met or not?

(Tang) By the people closest to the pain. By the people who are suffering and feel outraged. That is not put lightly because when people feel outraged, previously when they had no positional power or they were suffering from hermeneutic injustice or epistemic injustice – if they are suffering from these conditions, then the outrage naturally turns into divisiveness, into hate, into polarization, and into also the fragmentation that the professor just alluded to. So, the natural outcome of outrage is actually solidarity. If you feel that somebody has been wronged, the natural response is to prevent something like that from happening again. It is only when there is no visible recourse to address this injustice do people go to their isolated siloes of hate and discrimination, so the pro-social path is natural, the anti-social path is not, and outrage is natural, too. So, most of the social innovations based on the ideas of fast, fair, and fun are a reliable way to channel outrage into collaborative governance.

The faster one can channel the outrage, the easier it will be to communicate or to convey the necessary technological or scientific details because if people feel there is a strong injustice that is being suffered by somebody they know or they can identify with or they share experience with, they can put in a lot of cognitive resources into understanding the details just like any train accident or any earthquake or tsunami or whatever. People get into this mood. They want to try to understand everything because they naturally want to do everything it takes to prevent something like that from happening again. So, I am not saying that major disasters are the only way to move democracy forward, but smaller injustices and smaller outrages, when channeled into petitions and Presidential Hackathon topics. The Presidential Hackathon winners are often the direct result of the Kaohsiung gas explosion or a crashing helicopter from a remote island to medical treatment or things like that because people put in a lot of their energy trying to prevent something like that from happening again.

(Habuka) This is why we really need social innovation which allows people to raise small outrages to the public

(Tang) That is right.

Q8

(Habuka) The next question is the agile update of rules. We advocate a model in which rules and systems are updated in an agile manner in response to changes in society or maybe the small outrages from the people, but frequent changes to rules and systems have the disadvantage of causing confusion in practice or impairing predictability. So, what kind of measures should be taken to update governance mechanisms quickly?

(Tang) I mean that depends on what your expectation of predictability is. Because if we say very clearly, “This regulation or this interpretation will change every 60 days,” then it is actually quite predictable. It is not like it would confuse anyone. It is just people will change their time frame internally to expect an update after 60 days instead of previously after four years or after a fiscal year. So, in my experience, frequent changes are not a problem.

If you buy something from an e-commerce website, they will probably update every minute on whether it is shipped, whether its tracking number has been determined, and which truck has driven it to wherever or which place and so on, and if there are delays and so on, you can get real-time notification. Nobody seems to find them bothersome. There is no confusion at all, and mostly because there is a strong mental model that is underlying these frequent updates that people can still track with their mind’s eye. It is only a problem when the notifications and the changes are outside of the acceptable delta or the acceptable differences of their initial expectation and so on. So, it is all about expectation management. If you start from the very beginning like Taiwan does that our counter-epidemic measure will literally change every day at 2 p.m., then people adapt to that tempo.

(Habuka) In that context, do you think that population matters? For example, in Japan, we have maybe five or six times more people in our country compared with Taiwan. Does it matter to your mechanism or not?

(Tang) Well, I think population matters insofar that the common experiences pooled or shared by the stakeholders and constituents are commeasurable in the sense that my experience has a strong possibility when expressed in a sufficiently clear way to be understood by somebody else’s participation in the same polity. If due to cultural or civilization metaphor issues or religious or other issues, such communications were not possible in the beginning. For example, in Taiwan, we have 16 national languages and the parliamentary interpolations, if they are done in an indigenous language, they require an entire supporting system of real-time interpretation, captioning, and things like that. Without such systems, of course a larger, more diverse population poses a real problem when getting those changes propagated out through the society, and only when those assistive technologies like this eyeglass are in place for most people can we then talk about scale-free propagation, but of course it has an impact, but I think it is at most logarithmic. It is not linear. So, if you can partition it into some small-world networks just like what we were saying among the law and the technology community, then within each network, you can maintain a faster iteration cycle, but you still synchronize to a longer iteration cycle – maybe a quarter of something – on a larger network.

(Shishido) I have one question. Lawyers will read the record of this roundtable in a magazine, so I would like to ask, what do you think about the judiciary’s role in agile governance? I think the Constitutional Court of Taiwan contributed in interpreting, updating, and even setting some long-term goals, for example, by legalizing marriage equality. So, is the judiciary an element in your co-governance, and what changes do judiciaries need in this context?

(Tang) That is a great question. For example, Taiwan’s main judiciary innovation when it comes to direct democracy is the “good only for two years” referendum. If you pass a referendum, a national one, it is binding, but is binding only for half the term of the current legislature. It means that it is like a limited time simulation because for marriage equality, it is not easy to simulate in a more local way because people move all the time and there are also about cross-jurisdictional marriages and so on, but people can talk to themselves and say, “Let us try this social innovation of marring individuals and not families for two years, and if it does not work, well, let us go back to the drawing board because the two referenda that binds it are only good for two years anyway.” This is, as I mentioned, very different from the traditional, sortition-based, constitution-making citizens’ assembly which is good if not forever, at least for a decade or so. But we say very simply, “Two years,” and I think that is the time-based innovation. We are not changing the fundamental theories about referenda or about juries or about citizens’ assembly, but we are just saying, “Let us do it on a shorter, iterative time cycle.”

(Shishido) Thank you very much. Very instructive.

(Inatani) Just briefly. It impressed me that there is a layer. Every time, you mentioned layers and time span. That is the basic structure of your governance system in your image. We must share it because the last time we wrote the report – at least me – I did not care about the layers and time span so much, but now it is critical for me, so this is very inspiring. Thank you.

(Tang) Thank you.

Q9

(Habuka) Our l final question is global cooperation, namely how Japan and Taiwan or maybe other countries can cooperate on these kinds of agile governance or social innovations.

(Tang) I think the great thing about social innovation is that it is not dependent on particular products or services. Unlike treaty negotiations which take a lot of time – for example, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – social innovations are easy to replicate because like as soon as I described the SMS-based contact tracing to a governor who has tried an e-mail-based one to realize the same thing but without the fallback to flip phones and so on, they immediately realized how to improve their way of doing contract tracing, but of course Japan has almost eliminated the virus, so maybe you do not need it now, but maybe for the future.

The point here is that the ideas spread naturally, and just as our suggestion to cross-professional network policymaking, it is not a few arbitrators or mediators, but rather a series of frequent meet-ups such as this one, and so should it be for cross-jurisdictional issues when it comes to social innovations. I do believe that in, for example, the Open Government Partnership which Taiwan is actively participating while not being a full member, we are seeing a lot more stories like in OGP Stories where the stories are told in the structural way to maximize the reusability of individual ideas so that it is not about importing an entire system, but rather an idea like this interlocking time frame. This can be implanted in a vastly different way in Japan, but as long as the idea is sound, well, you probably will make more modifications and remixes that we can then learn from, so let us collaborate on the ideation stage more so than on the final text output or the compiled output of such processes.

* * *

(Habuka) Thank you so much. Finally, I would like to ask each of the participants for final comments.

(Tang) I do not have anything, but I must comment that I find this conversation really invigorating and very enjoyable, and we should do this more.

(Shishido) Thank you very much, Minister Tang. It was my pleasure. Especially, you talked about agile co-governance, not agile governance. It is very instructive, especially for me. I think we have to stress more on multi-stakeholder processes and participation value. In terms of mutual cooperation, we, Japanese constitution scholars, have had a long-time discussion with Taiwanese constitution scholars, including Prof. Yeh Jiunn-rong, the former Minister of Education.

(Tang) Yes, and also Minister of the Interior before that.

(Shishido) I hope intellectual exchange between Taiwan and Japan will continue in the future. Thank you very much.

(Tang) Thank you.

(Inatani) First of all, thank you so much for your very fruitful conversation. I could learn a lot from this fruitful conversation. Actually, I was impressed by two points especially. The first point is the mille-feuille-like society. Some of my colleagues told me that society becomes a mille-feuille style and I could not understand what the layer is, but today’s talk cleared me about what kind of mille-feuille we live in, and how to steer the mille-feuille society, we need more connections and more conversations and to overcome the risk of sectionalism. We also have to take into account the time span because, as you said, the essential value is not so quickly changed, and so we need a more solid framework for governance, but for minor or unknown things, we must have quick adaptation or quick change so that we can have a faster governance system, so we must mix them. In any case, I have learned a lot.

Maybe, it reminds me of Dewey’s pluralism. Dewey said that democracy needs everyone to become a specialist and we need to connect that, so I think we must revive his idea into our lives maybe. Thank you so much.

(Tang) Yes, definitely. Thank you.

(Habuka) Thank you so much for your great insights, Minister Tang. We strongly hope that we can collaborate in the future toward a better future through agile governance.

(Tang) Okay, excellent. I am looking forward to future collaborations.